Supporters of President Donald Trump will attempt to break the record for largest boat parade Saturday in Pinellas County.

source

Supporters of President Donald Trump will attempt to break the record for largest boat parade Saturday in Pinellas County.

source

[ad_1]

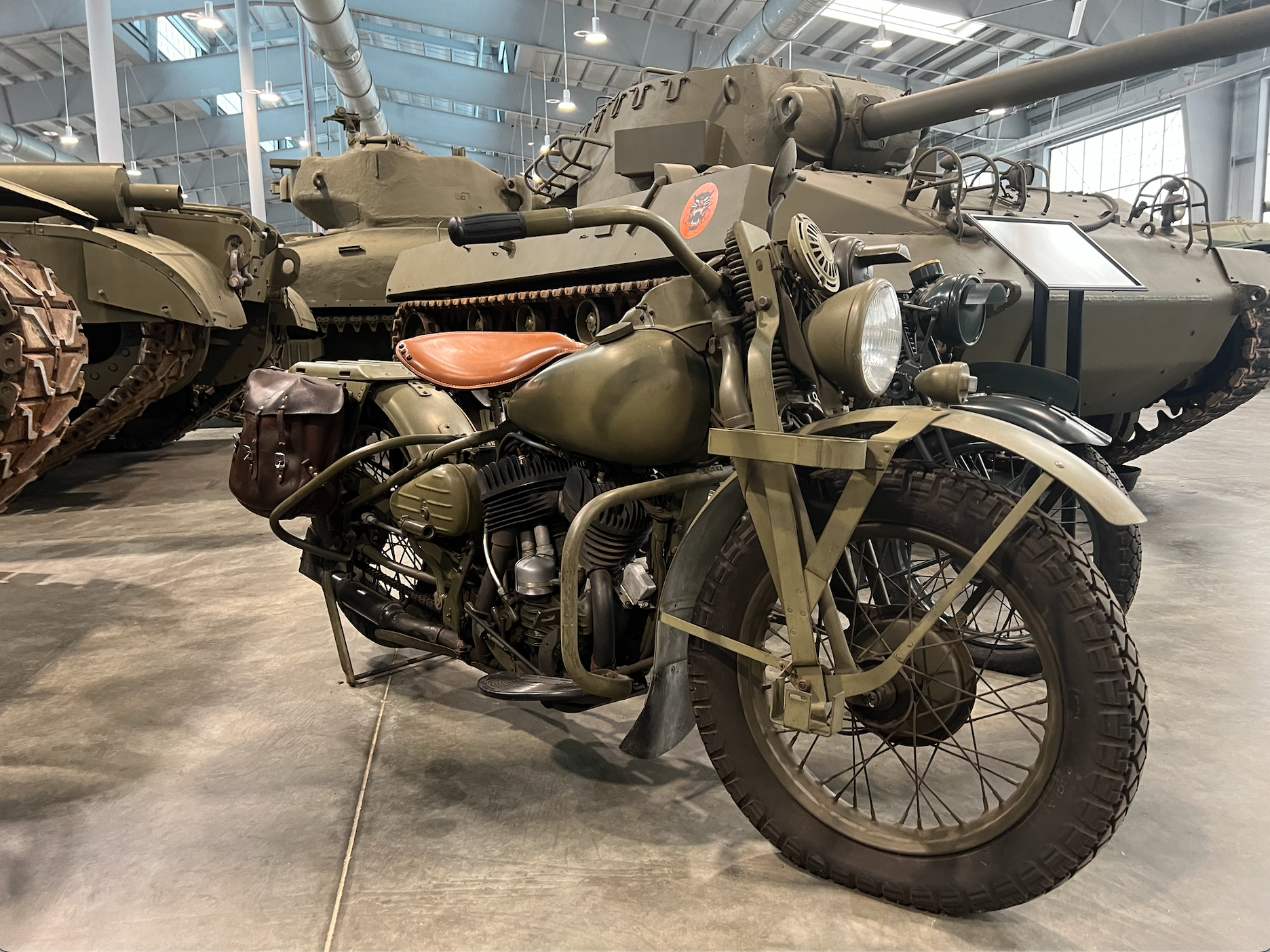

On the list of things the U.S. military has given civilian society, like sliced bread, duct tape, and microwave ovens, you can now add custom motorcycles otherwise known as “choppers.”

Often distinguished by their elongated handlebars and stretched-out front ends, choppers can trace their roots all the way back to World War II, when the son of William Harley, co-founder of Harley-Davidson, was training soldiers at Fort Knox, Kentucky. Decades prior, Harley-Davidson began in 1903 when William Harley and Arthur and Walter Davidson worked to build their first bike. Within just a few years the team was moving into their first factory, and in 1907, they began selling their motorcycles to police departments. Their production continued to increase, and in World War I, Harley-Davidson produced over 20,000 motorcycles for the military, according to the Las Vegas Harley-Davidson website.

That production more than tripled during World War II, when the company produced more than 90,000 bikes for the military. These military bikes offered an unprecedented level of mobility and maneuverability for transportation and scouting, all in a package that was easy to move from place to place.

Rob Cogan, a collection curator at the U.S. Army Armor and Cavalry Collection at Fort Benning, Georgia, told Task & Purpose in April that Harley-Davidson first started building bikes for the U.S. Army in the 1920s and 1930s. At the time, the Army cavalry branch was buying up “tons of motorcycles,” Cogan said. Between the 1930s and 1940s around a third of Army cavalry scouts were on motorcycles.

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest in military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

Among Fort Benning’s collection, housed in a giant warehouse on-post, are two motorcycles, one of which is believed to be one of the last the Army bought. It’s in nearly perfect condition, Cogan said, with only 11 hours on the engine. The motorcycle next to it is a British BSA, which the British Army used around the same time.

“When you tell young scouts today, they’re like ‘Oh man why aren’t we on motorcycles?’ And it seems really great until you realize it has no major weapons systems, it has no armor on it, especially when during this timeframe it couldn’t carry the heavy radios they had,” Cogan said.

During World War II, cavalry scouts were trained on motorcycles for various purposes outside of reconnaissance, including providing support and moving equipment or messages among units. And who better to instruct soldiers on that than 1st Lt. John Harley — son of William Harley, of Harley-Davidson fame. 1st Lt. Harley was still “very much a motorcycle enthusiast,” Cogan said, so in his free time at Fort Knox, he would tinker with the bikes to show soldiers what to remove or modify to make them go faster.

Fast forward a few years at the end of the war, and soldiers had found a match made in Heaven: they had some money in their pockets, and the motorcycles that were used by the cavalry were being “sold for dirt cheap,” Cogan said. But the motorcycles also had a number of things your average rider doesn’t need — various racks and things for storage that the Army wanted, but that weren’t really necessary for civilian use.

“They didn’t care about having a blackout light that you’d use in tactical situations, they didn’t care about the rifle rack, so they chopped some of those off and that’s where you get the term ‘American Chopper’ coming from because of these modified Army motorcycles,” he said. “So really World War II and the U.S. mechanized cavalry that really creates the American motorcycle culture today.”

It didn’t take long for the civilian world to catch on to this trend of “chopping” and modifying motorcycles for style and speed. Whether for looks or drag racing, the style caught on with riders across the country in the 1950s and 1960s, ultimately becoming a countercultural icon in its own right.

Harley-Davidson was later awarded two Army-Navy “E” Awards for Excellence in Production during World War II. And while the military has come a long way since then, Cogan said it stands as a reminder of the way military and civilian culture have intertwined in the past.

“The military culture in our society — it permeates more than you think,” he said.

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.

[ad_2]

Source link

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/6C25BBKXNFFTJCFBSQW33LC7CA.jpg)

[ad_1]

Remains of a U.S. Marine who was wounded on the Pacific Ocean island of Saipan during World War II have been identified and he will be buried in his hometown of Nashville, Tennessee, officials said.

Marine Corps Reserve Cpl. William R. Ragsdale, 23, is scheduled to be buried Aug. 6 in Nashville, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency said in a news release Friday.

Ragsdale was a member of Headquarters Company, 1st Battalion, 24th Marine Regiment, 4th Marine Division during the battle on Saipan in June 1944, the agency said.

Ragsdale was first reported as wounded in action. He was unable to be found during the chaos surrounding the battle and its aftermath. His status was changed to missing in action, and then later deceased, the agency said.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/H7D373QPP5DD3AL3VN6PJGUWYI.jpg)

Investigators searched on Saipan but could not find Ragsdale’s remains. He was declared nonrecoverable in September 1949.

Later, remains designated as Unknown X-6, 27th Infantry Division Cemetery, were recovered from Saipan and buried in the Philippines. Those remains were sent in 2020 to a Hawaii laboratory for dental, anthropological and DNA analysis,

The remains were found to be Ragsdale’s and he was officially accounted for in April, the agency said.

[ad_2]

Source link

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/ZDWXTPNJ7NDQXCMCBMDYST5BOQ.jpg)

[ad_1]

Billy Earl Kirby’s own blood helped give Italy’s Rapido River its second name, “Bloody River.”

Kirby, a native of Osage, Texas, was a 23-year-old Army infantryman when he was injured in one of the fiercest battles between American and German forces in World War II.

“Jan. 21, 1944. I will never forget that,” the 101-year-old Kirby said from his room at The Landing, an independent living facility in Wilson.

“It was the battle of Cassino. It was probably one of the biggest battles in Italy,” added Kirby, who formerly lived in Zebulon. “There have been a lot of papers, a lot of books about it. They called it the Bloody River and so forth.”

Kirby, a member of Company K, 143 Infantry Regiment, 36th Division, was a machine gun section leader in the rifle company.

“Our general didn’t want to cross the river at the spot that [Lt. Gen.] Mark Clark picked. He said it would be totally impossible because it was so heavily defended,” Kirby recalled. “Across the river was just as flat as could be over the fence. He wanted to cross further up river where the river was not as deep.”

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/DNHWPB6OKZGIDPWOQCFAYLMYXY.jpg)

But the soldiers went across where they were ordered to cross.

“That’s where we were slaughtered,” Kirby said. “This was about the only battle in World War II that I know of where there was a truce. Germans requested for us to come over and pick up our dead. Our division was about destroyed. Out of our company of 200 men, 27 survived. Our National Guard from Texas was destroyed. My machine gun section, the last battle I went into, I didn’t have a man who was there to start with. I had lost them all.”

Some 1,330 Americans were killed or wounded and 770 were captured, while German casualties amount to 64 killed and 179 wounded.

It was one of the U.S. Army’s largest defeats during the war, Kirby said.

Kirby was shot in the shoulder.

“It paralyzed my arm. It severed the nerve,” he said, gesturing with his left arm because some 78 years after his injury, he still can barely raise his right arm.

“It was night when I was wounded, and I guess I was losing so much blood and sleepy,” Kirby recalled. “I just wanted to lie down and go to sleep.”

Two of Kirby’s fellow surviving soldiers came to his aid.

“How we got back across that river, I don’t know,” he said.

Kirby was in the hospital for two years. The first six months were in North Africa and the last 18 months were in Texas.

“I was in a body cast for 18 months, my arms like this. It was the only kind of cast that would hold it,” Kirby said. “I don’t know how they saved my arm. I thought I would lose it. We had some pretty good doctors back then. They did a lot of experimenting. They tried things that they wouldn’t try. That’s where they learned a lot in World War II.”

Kirby still doesn’t have much use of his right arm.

“I can’t raise it up. It shakes all the time,” he said. “If I can touch something, I can stop it from shaking. I don’t feel anything. The nerve is dead.”

Somebody asked Kirby if he was scared during his time in the service.

“I only got scared in World War II one time. I got scared when I got on the boat and I stayed scared until I got off coming home,” he said. “There were some times I was more scared than others. I wouldn’t say we were scared as much in combat. You were careful. But the first time, I was.”

Kirby said he and his fellow soldiers had great camaraderie and for many years, the survivors would gather for reunions at both the company and regiment level.

“We were extremely close,” he said.

When they got together, they would never discuss the war.

“The only time we ever talked about the war was the funny things that the happened in war, but we never talked about the fighting,” Kirby said. “We just didn’t want to bring that up to your mind.”

:quality(70)/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-mco.s3.amazonaws.com/public/G6DASS4OCJAG3OTSXRVBOLEELM.jpg)

After his discharge from the Army as a staff sergeant in January 1946, Kirby went on to work for the Veterans Administration for several years.

In 1960, the Bronze Star recipient went to work on veterans’ issues for the U.S. House of Representatives. He remained in that role until he retired in 1977.

Kirby was elected national commander for the Disabled American Veterans in 1988.

Kirby called war “the most horrible thing.”

“I can’t understand why politicians want to start a war, why human beings want to start a war. It’s their egos,” he said. “People like dictators, they are the ones you have got to worry about. I don’t think any democratic countries will ever want to go to war. You get more civilians killed than you get military people killed.”

In 2014, a quote from Billy Kirby was unveiled on the walls of the new American Veterans Disabled for Life Memorial in Washington.

“I shall recall with respect those who fought with me and were scarred with bullets, left limbless by bombs. I shall recall with humility those who were stronger and braver than me, and I shall recall the celebration and joy our nation’s heritage of selfless sacrifice and commitment to the common good,” Kirby is quoted as saying.

[ad_2]

Source link