[ad_1]

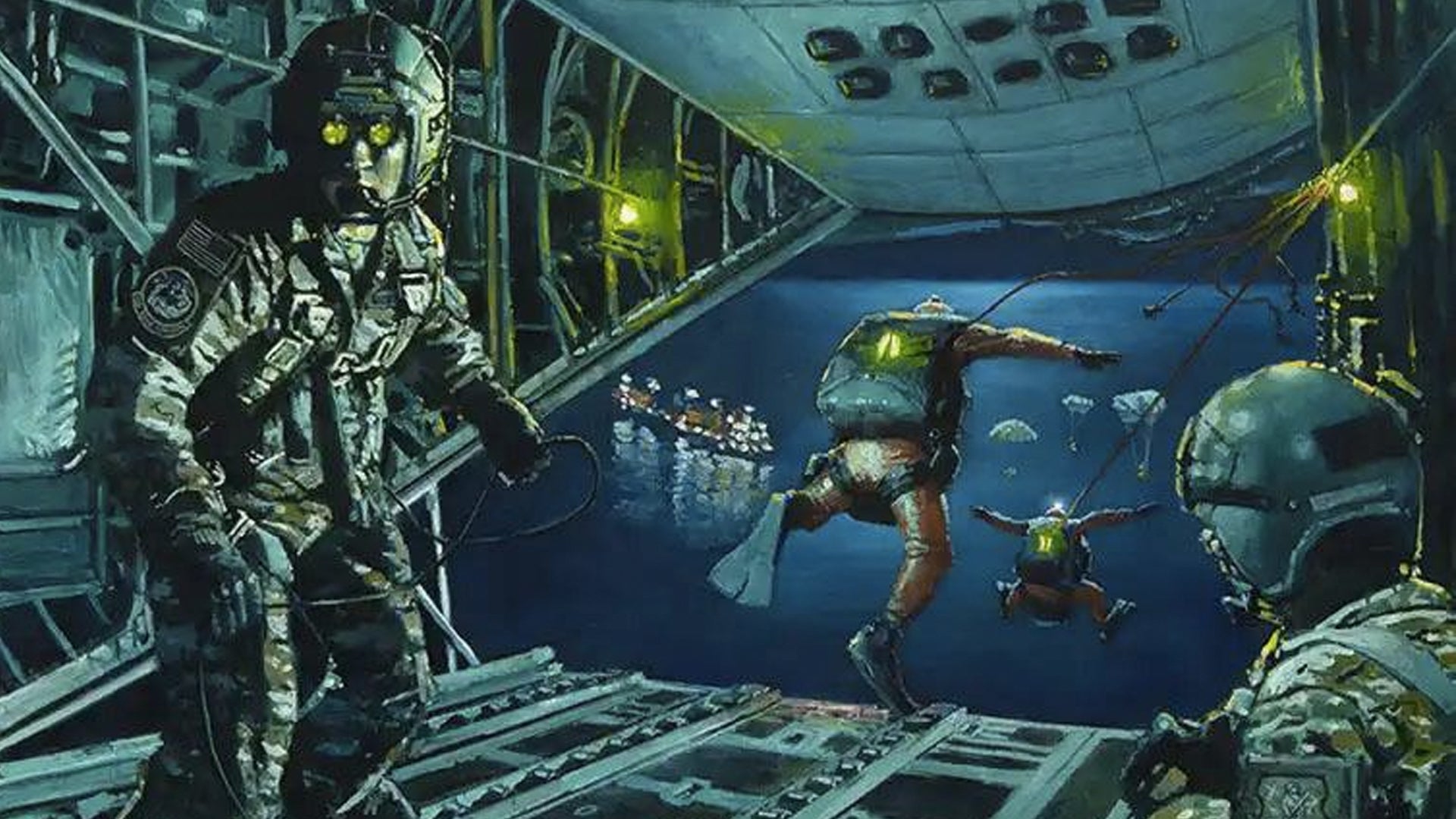

From the Revolutionary War Battles of Lexington and Concord to the Afghanistan battle of Takur Ghar, the National Guard often immortalizes its most significant missions in the form of oil paintings. Last month, the Guard unveiled the latest such painting, which depicts a 2017 mission where seven airmen with the New York Air National Guard jumped out of an airplane in the middle of the night over the middle of an ocean to rescue complete strangers suffering from severe burns. It was a complicated mission that the airmen pulled together in less than a day, but they pulled it off, even when things went sideways.

“The amount of complexity in that mission just can’t be overstated,” said Col. Jeffrey Cannet, the commander of the New York-based 106th Operations Group, who piloted the HC-130 search and rescue aircraft on the mission, in an Air National Guard press release. “The fact that these guys had to do that, all out there, alone and unafraid, getting it done, was just a testament to their skill and ability.”

The incident began early in the morning of April 24, 2017, when an explosion aboard the cargo ship Tamar badly injured two sailors and killed two more. The crew of the 625-foot vessel, which was in transit from Baltimore, Maryland to Gibraltar, at the western edge of the Mediterranean sea, contacted the Coast Guard, which then contacted the New York Air National Guard and its 106th Rescue Wing. With its HC-130 search and rescue planes and trained pararescuemen, the 106th was best prepared to respond to the emergency. Still, the Tamar was about 1,500 miles off the New York coast, and that distance was a stretch even for these airmen.

“1,500 miles out … was a bit out of reach for anybody else, and quite frankly I think everybody thought it was out of reach for us too,” Cannet said at the unveiling and award ceremony last month, where each airman received an Air Force Commendation Medal for heroism. But he and his men thought differently.

“No we got this, this is not an impossible mission,” he said. “We got the skills, the equipment, the training. We can pull this off.”

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

The 106th could not formally be assigned to the Tamar rescue because it was a civil search and rescue mission, the wing wrote in a press release, but all the airmen involved volunteered for the flight anyway. Those airmen included combat rescue officers Lt. Col. Edward Boughal and Maj. Marty Viera; and pararescuemen Master Sgt. Jordan St. Clair; Senior Master Sgt. Erik Blom; Master Sgt. Jedediah Smith; and Staff Sgt. Michael Hartman.

Also called ‘PJs,’ Air Force pararescuemen are elite specialists in search and rescue and combat medicine who train to rescue downed pilots or special operators cut off behind enemy lines. Combat rescue officers are the commissioned leaders of PJs. But before these highly-trained airmen could rescue the sailors, they first had to do some shopping for medical and surgical supplies at local hospitals.

The mission got a little dicier shortly after takeoff, where a hydraulic failure aboard the HC-130 threatened to end the mission before it could fully begin. The flight engineer, Master Sgt Keith Weckerle, managed to mitigate the problem, which he might have been accustomed to due to the unit’s aging aircraft.

“The wing accomplishes its mission in both combat and peacetime with aging aircraft, some dating back to the ’60s,” the 106th Rescue Wing said in a 2017 video about the mission.

Luckily, the HC-130 made it over a thousand miles from the 106th’s base on Long Island all the way to the Tamar, which was pretty much right in the middle of the Atlantic by that time. But getting to the ship was only the first step in the complicated mission plan. Next, they had to drop equipment bundles and two inflatable Zodiac boats on target in the dead of night. Then they would parachute out of the aircraft, swim to the Zodiacs, get in, pick up the floating supplies, get to the Tamar and board it via rope ladder with 15-foot waves tossing them up and down.

Jumping out of the aircraft would be its own challenge — the HC-130 was 1,400 feet above the dark waters, which is a comparatively low altitude to jump from. The low cloud ceiling and urgency to get to the dying sailors below made it worth the risk, the airmen decided, but it was still a risky operation. “Perilous” weather conditions and high seas also contributed to making the jump an “extraordinarily dangerous situation,” said Senior Master Sgt. Tom Pierce at the ceremony last month.

“I definitely found a moment to pray,” said Viera, one of the combat rescue officers, in a 2017 press release. “I (wondered), did I kiss my wife and son goodbye enough? I was like, God, if this is my time to go, I guess this is it. But please, I would really like to make an impact on these people’s lives.”

Though each of the airmen wore flashing beacons and red and green chemical lights, the risk of a mid-air collision was very real.

“Collisions can be potentially fatal at that altitude,” said Boughal, the other combat rescue officer. “There were a couple of moments where I was thinking, ‘Where are my guys?’ because it was so dark.”

It was risky, but Smith, one of the PJs, was pumped.

“I distinctly remember on the ramp of the C-130 … and Jed’s eyes lit up after the green light illuminated that sent the first team into the inky blackness of the night,” said Boughal. “He turned to me with a big smile, fist-pumped me and yelled out ‘we’re doing this!’ I remember thinking ‘glad he’s on the team.’”

It was good Smith was pumped, because the going was about to get tough. The seven airmen made it onto the Tamar, but now they had to keep two severely injured men alive for three days as the ship made its way to the Azores, an archipelago about 870 miles off the coast of Portugal. There, Portuguese helicopters would pick up the sailors and ferry them to a hospital, but they had to live through the journey first.

“When we got there we found the crewmen badly burned on their face, arms, legs and hands,” said St. Clair, one of the PJs. “The initial report was that they were conscious, talking and were mobile. But we knew the end state. Their lives were absolutely at risk.”

One of the sailors, a Slovenian, said it was getting harder for him to breathe, so the airmen slid a tube down his throat to hook him up to a ventilator. The airmen then took 90-minute shifts watching over the patients while removing dead tissue, reducing pressure on the wounds, and making incisions on badly burned tissue to establish blood circulation., according to a press release. After a few hours, the airway of the second sailor, a Filipino, “became compromised but was too swollen to allow a tube to pass,” the press release said. Thinking fast, the pararescuemen performed a cricothyrotomy, where medical providers cut a slit through the patient’s throat through which they can pass a breathing tube.

“Now here’s this poor guy, pulse-ox crashing, literally taking his last agonal gasps, and up steps Jordan [St. Clair] to calmly and methodically find his airway, place the tube, and save this guy’s life like he was tying his shoelaces,” Boughal said at the ceremony. “Jordan has ice in his veins.”

Over three days, the airmen kept vigil over the patients and managed their fluids and pain levels. It helped that they could call Lt. Col. Stephen “Doc” Rush, the 106th Medical Group commander, for his insight. But keeping the patients alive was not the final challenge: the airmen also had to figure out how to lower the patients three stories to the ship’s deck so that they could be hoisted onto the Portuguese helicopter. They managed by rigging up a belay system using ropes, and then three of the airmen went with the patients aboard the helicopter to keep them alive on the way to the hospital.

“What they ended up having to do on that ship that day was remarkable,” Cannet said, about the medical care his airmen provided.

Even after the helicopter departed, the danger was not over for the four airmen still on the Tamar, who had to get down onto a waiting tugboat in high seas. At one point the waves crushed the tug against the Tamar so hard that it cut the rope ladder the airmen were using in half. With the ladder gone, the airmen jumped into the tug one by one and made it out safely. The patients also survived and are alive today.

“Those two men are alive and enjoying life today because of our ability to provide a capability that very few organizations can,” said St. Clair at the award ceremony.

The idea of immortalizing that mission in a painting came from Chief Master Sgt. Brian Mosher, the 106th Operations Group superintendent, said Maj. Michael O’Hagan, the wing’s public affairs officer, in a press release. O’Hagan knew a painter named Todd L.W. Doney, a former illustrator who teaches art at County College of Morris, New Jersey. Doney charges up to $15,000 per canvas, but he “agreed to do the job for materials and time only.”

The artist drew from photographs of the mission and from the memories of the aircrew and pararescue team who were there that day. The airmen made sure the parachute cords were the right color, that there were the right number of cargo rollers on the HC-130 deck, and that the loadmaster’s uniform was the right pattern.

“I think what sticks out most in my mind, is you look at the ship, and you see the guys out there,” said 1st Lt. Jamie Bustamante, the loadmaster in the painting. “I do remember seeing all that.”

For his part, Doney said that what makes the painting special is the heroic deed it portrays.

“It wouldn‘t be a great painting unless those guys did what they did,” he said. “It was really awesome to honor these guys who jumped out in the middle of the night to save lives.”

The latest on Task & Purpose

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.

[ad_2]

Source link

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/T56ADX64ANDYNP5MWRKCULXRZA.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/QBYJTGYCQBHSVITAL32RAO7HAA.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/YVREBMCGTNFNTI6PSBKVQDR7CU.jpg)